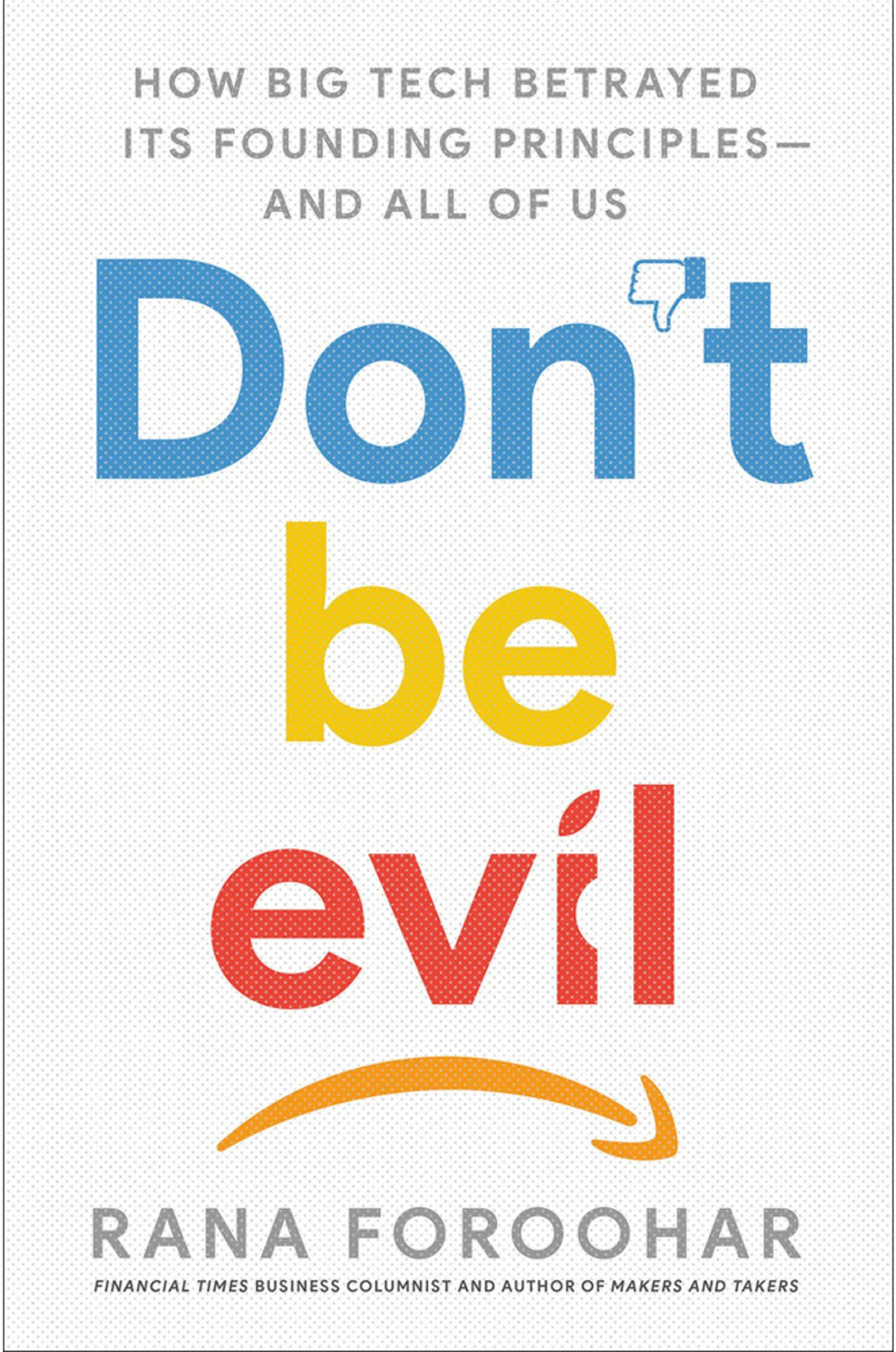

Don't be evil

The author is Financial Times global business reporter. She had short stint in venture capital firm in Landon during dot com boom and bust so there’s real world experience there. The book is focused on anti-competitive practice and predatory pricing more than negative effects on public health and democracy like the previous book “Zucked”. Also the criticism is levelled more broadly including Apple, Amazon and others. The followings are what I find interesting and new.

Benefits of big tech

It has connected the world, helped spark revolutions against oppressive governments (even as it has also facilitated repression), and created entirely new paradigms for invention and innovation. Platform technologies allow many of us to work remotely, maintain distant relationships, develop new talents, market our businesses, and share our views, our creative expression and/or our products with a global audience. Big Tech has given us the tools to call up a variety of goods and services—from transportation to food to medical treatment—on demand, and generally live in a way that is more convenient and efficient than ever before. It, however, has brought immeasurable but often overlooked harm.

Harm…

Depression

Mobile games and apps are designed to make us believe there’s a chance we could be missing something important. And that is what keeps us checking our phones constantly: around 2,617 times a day, according to one study. this has a terrible effect on our mental health, increasing stress and anxiety levels and even risk of illness.

The average teenager, who spends 7.5 hours a day playing with screens and phones. Is it any wonder they are more isolated, less social, and more prone to depression than previous generations? As scary as this is, it’s even scarier that these conditions can actually be monetized by the platforms that create them. In 2017, Facebook documents leaked to The Australian showed that executives had actually boasted to advertisers that by monitoring posts, interactions, and photos in real time, they are able to track when teens feel “insecure,” “worthless,” “stressed,” “useless,” and “a failure,” and can micro-target ads down to those vulnerable “moments when young people need a confidence boost.” Think about that for a minute. It’s an endless, wanton commodification of our attention, with little or no concern for the repercussions for individuals.

Attention deficits

A wealth of information means a dearth of something else, as Nobel Prize–winning economist Herbert Simon once put it. “What information consumes is rather obvious: It consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention, and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume grow.

Privacy

Facebook Android app logs users’ phone calls. It was an invasion of privacy on a new level—but it also created more data that could be mined, which increased Facebook’s ability to grow i.e. their bottom line.

The most valuable use case of user data is anticipation of future purchase intent based on a detailed history of past behavior. When users get ads for things they were just talking about, the key enabler is behavior prediction based on combined data sets

Democracy

The online platforms were, by this definition, public spaces, the companies who ran them were not responsible for what happened there. Today, Facebook, Google, and other companies absolutely can—and do—monitor nearly everything we do online. And yet, they want to play both sides of the fence when it comes to taking responsibility for the hate speech, Russian-funded political ads, and fake news that proliferate on their platforms.

The academic Aleksandr Kogan created a survey app that was deployed on Facebook, and he used it to collect information not only on the 250,000 people who actually took the survey—but also on the 87 million more users they knew. Cambridge Analytica then used that information to deploy ads that may have helped tip the 2016 U.S. presidential election in favor of Donald Trump. That’s the network effect in action, at its most nefarious.

Justice Department investigations have now shown, these entities used U.S. technology platforms, most notably Facebook, which was found to have accepted $100,000 in advertising from Russian actors, but also Instagram (owned by Facebook), Twitter, YouTube (owned by Google), and PayPal to execute their crimes.

These problems—filter bubbles, fake news, data breaches, and fraud—are all at the center of the most malignant—and profitable—business model in the world: that of data mining and hyper-targeted advertising

The political influence Google wields.

Stop Online Piracy Act. A day after the bill was introduced, Google put what looked like a big black box across its logo, with the words TELL CONGRESS: DON’T CENSOR THE WEB. The message let people click straight through to a blank email already addressed to their congressperson, which resulted in the crashing of congressional email servers. The bill was pulled within three days.

This move is currently being used in Australia trying to mislead general public to go against the new law under consideration. It is designed to force Google and Facebook to share ad revenue with news outlets i.e. content creators.

Anti-competitive practice

Big Tech firms, use behavioral persuasion, troves of personal data, and network effects to achieve monopoly power, which ultimately affords them political power, which in turn helps them hold on to their monopolies.

Google vs Yelp

When Google’s algorithms deemed local websites, such as Yelp or CitySearch, relevant to a user’s query, Google automatically returned Google Local at the top of the results. That meant preferred placement for Google own services at the top of search results. Google is NOT a neutral arbiter of information.

Amazon vs Third-party sellers

Amazon owns and runs the platform, it also sells on the platform i.e. directly competes with third-party sellers. They know what products, colour, configuration sell well to whom and what group. They know infinitely more than third party sellers. They use this information to undersell third-party sellers. They can steer customers to their products through their page rankings, or place their product ad in a more prominent position.

Uber

Uber touts its drivers as “free and independent” contractors, yet thanks to its automated algorithmic management system, the company is able to control how they work and penalize them when their behaviors deviate from what might be most profitable—for Uber.

Big Tech enjoys several natural advantages that breed monopoly power: information asymmetries, the network effect, the ability to easily copy the ideas of smaller competitors in an open-source environment, gatekeeper rents (even if they are in the form of data, not dollars), and the legal and political muscle the largest players can exert at will in Washington.

How could platform giants, which grow to scale in a world in which the usual economic laws of gravity cease to function, be regulated? These are pressing questions, because as we’ve already seen, not just from Amazon or Google, but from start-ups like Airbnb and Uber as well, digital giants can come from out of nowhere and disrupt incumbents, consumers, workers, and even entire cities in one fell swoop, at a pace that would have once been unthinkable

To alleviate harm, the author recommends the followings.

Communication decency act section 230, which protects internet platforms from liability of whatever users are doing on the platforms, needs to be reviewed. Given the technological, political, and financial power internet platforms wield, they should be able to do something about the exploitation of the platforms to incite violence or any other social harm. As it stands, there’s no incentive for them to act.

A separation of platforms and commerce to create a more equitable and competitive digital landscape. The power of Big Tech is all too reminiscent of the power held by nineteenth-century railroad barons. They, too, dominated their economy and society. And they, too, were able to price gouge, drive competitors out of business, and avoid taxation and regulation, largely by buying off politicians. Yet eventually, they were curbed by a number of regulatory changes.

A digital dividend paid by data collectors to the owners of this resource—all of us. It is akin to the way Alaska and countries including Norway have created wealth funds into which a percentage of revenues from commodities are invested for the benefit of future generations.

A digital bill of rights that would assign possession of data to its true owner.

Checking email less, cutting off most of social media, and turning devices off after dinner.